Related content

AUTHOR

Heidi Sopinka

Heidi Sopinka is the author of The Dictionary of Animal Languages,…

Discover

It’s okay for men to make bad art. There’s no price on their head for doing it … Nothing for men is pre-determined, except their chance at great success.

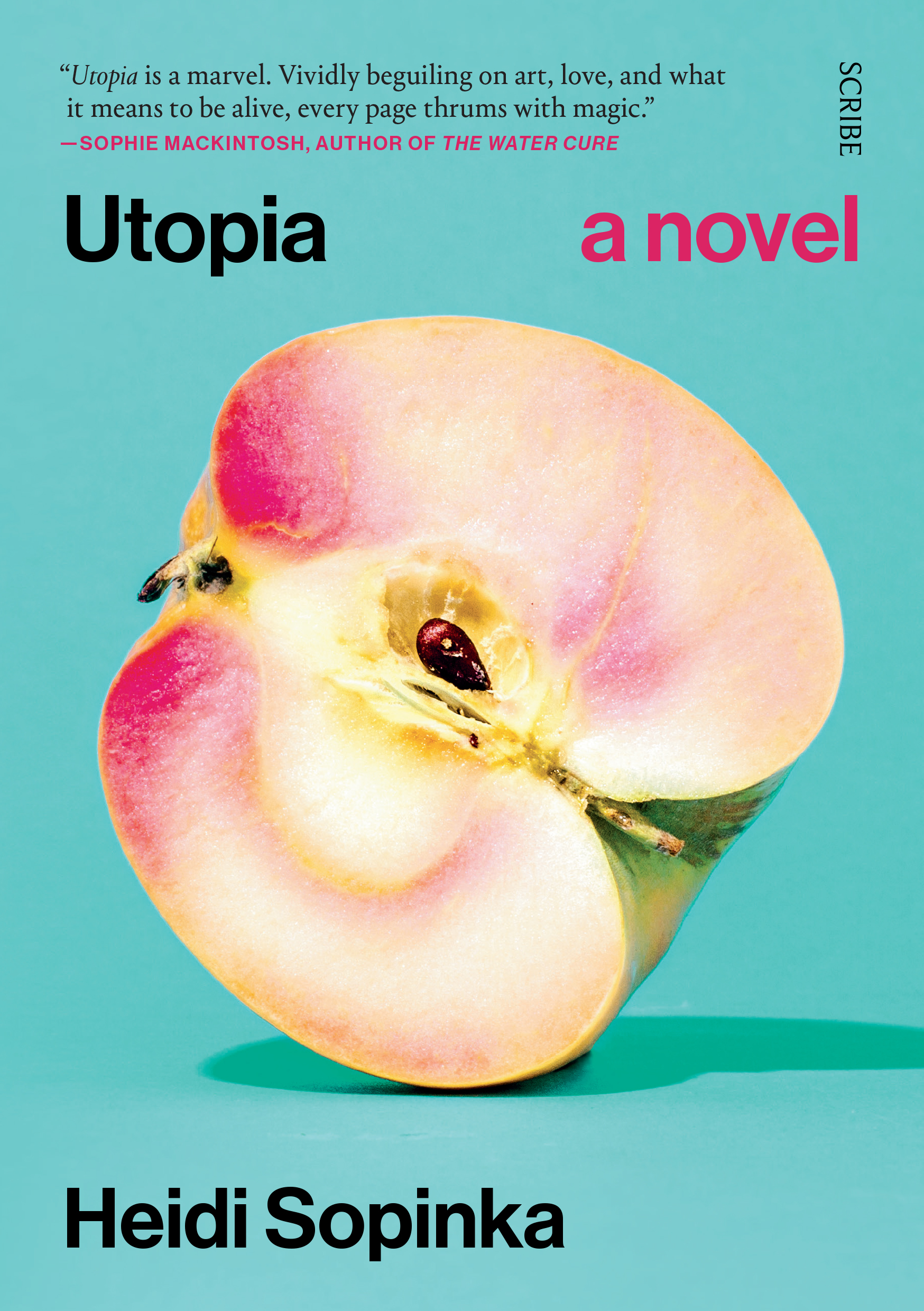

Utopia is a new novel by Heidi Sopinka, the author of The Dictionary of Animal Languages. Set in the 1970s in Los Angeles, it follows Paz, fresh out of art school in New York, who steps in to take the place of her new husband’s recently — and mysteriously — deceased wife, Romy. But in this new life, Paz is increasingly obsessed with the woman she has replaced, and a disturbing picture starts to emerge as the circumstances around Romy’s death are revealed. Important through this all is art, and the reality of existing in the male-dominated art scene of the time.

Of the book, Saba Sams (author of Send Nudes) has said, ‘Utopia is interested in life as performance, in the ways that we attempt to transcend our own bodies, and in what it means to be a woman artist in a world that is run by and for men. Set against the backdrop of the arid California desert, full of scalding cups of diner coffee and burning tarmac highways, this is a book as seething as its parts.’

Find an interview with the author here, and read on for a short excerpt from this fascinating book.

———

UTOPIA

THE NIGHT WAS HOT AS ever. I sat on the bed in Milt’s room with the door closed, my back against the wall, but the party was still loud. Itwas the kind of party we tried to avoid. Billy had grown tired of them, and I’d been working alone in the desert, jangly and on edge, though it was the most cathartic thing I’d ever done. Keeping something this big away from everyone I knew felt something like safety. Then I had you. But Milt, Billy’s gallerist, was throwing the party for him, so we went. We brought you because you were barely seven weeks old.

The building almost felt like New York — a 1920s enormously high-ceilinged corner apartment, with big windows on two sides, except that what we looked out on were the tops of tall skinny palms. Nixon had kept an apartment on the sixth floor of the building, which lent the whole place a slightly depraved aura. Milt’s apartment was all neutral Scandinavian glass and metal, done over by his wife, Makiko, who didn’t live there anymore. She’d left him so quickly she had to pack her things in plastic bags and hire a limo because she didn’t drive. People thought she was a saint to put up with Milt, until she couldn’t and left him for another gallerist, one who wasn’t a speed addict.

I had once been told that I sparkled, sparkled so brightly, but right then I felt like I wasn’t even that good at my own life. My head ached. I opened the night table drawer. It rattled. I swallowed some aspirin and washed them down with gin. Sitting on the bed with you, I put my face near the top of your head and inhaled. You settled into the crook of my arm. We were still getting to know each other. I was thinking about how far away I was from the clean truth I wanted to live. But I couldn’t make a living from art. At least not the kind I made.

I’d left Billy in Milt’s living room surrounded by women flirting with him as though I wasn’t there. Entourages had always been good for his mystique. Everyone was gathered to celebrate him in a way I knew I could never be celebrated, even though my work was as good as his. It shouldn’t have been a contest, though, because how could it be? I was

in here feeding you, understanding that everything had somehow come down to me. It made my pulse surge. I slugged back my drink and looked at the crack of light coming from under the door. I couldn’t help but think he’d won.

I had always been saving drinking for old age because it wasn’t compatible with my ambition, or new motherhood, but tonight I made an exception. As I was feeding you, the door flew open and a woman in a pleated silk dress looked at me and said, ‘Shit, sorry,’ and shut it abruptly. Her face said it all. Alone, tits out, baby. It was disgusting.

When you finally fell asleep, I wasn’t sure what to do. I felt a bit slurry from the gin, from sleeping in fragments. You were too new to be left on the bed. You could roll off. Could you roll off? You were so delicate and long. I decided on Milt’s dresser. People do it, I thought. I pulled out the bottom drawer and placed you as carefully as I could on top of Milt’s shirts. I lingered for a moment and then kissed your head. I did up the buttons on my velvet jacket and walked out dazed and blinking at the lights, a bit stunned by the change of frequency. There were two stereos playing, people talking, communication getting lost in a mix of machines and voices.

I sidestepped a low table crammed with plates heaped with shrimp shells and chicken bones, ashtrays, and martini glasses. ‘Romy,’ a woman I didn’t know said, reaching for my arm. She was wearing a dark men’s jacket and had tucked her long hair into the collar the way I often did. I hadn’t physically submitted to pregnancy. Even though I’d felt all womb, that my guts and vital organs were all exposed, I’d worn the same clothes. Women liked how unconcerned I was about what other people thought, my friend Fina had told me. Apparently, they were all sick of sucking into tight satin, lipglossed, feeling trapped. Fina said those women would never get what they wanted, though, because it was something only I could pull off. As if freedom was something to pull off.

‘Billy says you are working on something big in the desert,’ the woman said.

‘He told you?’ I said stiffly. It was unsettling looking at someone dressed like me.

‘How did you think of it?’

I picked up a glass, glittering from a silver tray offered to me by a young woman — a girl, really. The light was burned out in the bathroom but there was someone serving expensive champagne off a silver tray. That was Milt.

‘It went from the divine to feeling like something real,’ I said.

‘I didn’t know people could decide to make that kind of thing happen,’ the woman said.

‘What do you mean, decide?’

Milt came toward me through layers of smoke, offered me a cigarette, and leaned over and lit it with his gold lighter. His expensive suit jacket looked a bit rumpled, as though he might have slept in it the night before. The woman clinked his glass, saying, ‘Happy holidays.’ Milt held it up and nodded. ‘To the season of tinsel, depression, and alcohol.’ The woman’s face fell. She quickly made her way to a nearby group of artists.

Milt turned to me. ‘You’re looking good, Romy.’

‘I am good, Milt. I’m an ox.’ I took a drag of my cigarette. ‘This is new,’ I said, facing the giant, red word-piece of Juke’s that said, ANGEL.

‘Place needed some fucking color,’ Milt said, exhaling. A slight, I presumed, to Makiko’s monochromatic minimalism.

‘So, when are you going to let me see this mysterious work of yours,’ he said. ‘You know, I could represent you instead of that alpha dog in a caftan you’ve been showing with.’ He took a sip of his drink and swallowed. ‘Get you really out there.’

I looked at Milt. I was an inch taller than him. I hated this vile angle of the business. ‘The thing is, I want to make the kind of work that seems like no one made it.’

‘Fantastic,’ he said excitedly.

‘I thought you only worked with men.’

‘Listen. I don’t want to be categorical, but there are two kinds of women.’ He paused, looking at me. ‘You’re the other kind.’

I downed my drink, and Milt poured me another. The champagne was doing its job. I felt an almost perverse vitality, already a bit unsteady on my feet. Across the room, Billy was talking and smoking by the window with a woman who was looking up at him. They always wanted the part of him that was no good.

‘Buck up,’ Milt said, taking a pull on his cigarette. ‘You know you could wipe the floor with him anytime you choose.’ He said it teasingly, but it made me sullen. Milt was smart about art, but he was a lout. If I thought about it, I knew no one in the art business who acted with a proper adult response. I’d never told Billy, but often when he left the room, Milt put the moves on me.

‘It’s confusing for him,’ Milt said leaning closer, ‘that the coltish beautiful woman he married has turned out to be this spooky genius.’ Billy saw us. He wasn’t a jealous person, but I knew he had a thing about Milt. He came over and took the glass of champagne out of my hand and banged it down on the table a little too loudly, then pulled me aside by my elbow. We squared off in lowered voices.

‘I just want to have a conversation,’ he said.

‘This isn’t a conversation,’ I replied. ‘It’s warfare.’

———

Find Utopia online or in bookshops now.

It’s okay for men to make bad art. There’s no price on their head for doing it … Nothing for men is pre-determined, except their chance at great success.

Los Angeles, 1978.

When Romy, a gifted young artist in the male-dominated art scene of 1970s California, dies in suspicious circumstances, it is not long before her art-star husband Billy finds a replacement.

Paz, fresh out of art school in New York, returns to California to take her place. But she is haunted by Romy, who is everywhere: in the photos and notebooks and art strewn around the house, and in the eyes of the baby she left behind.

As Paz…

Heidi Sopinka

Heidi Sopinka is the author of The Dictionary of Animal Languages,…

Discover